The poor have a right to eat

|

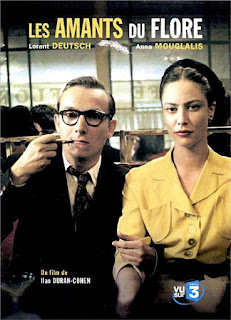

| photo by Carol Stampone |

The

poor also need to eat. We know it. However, it is easy to forget that the poor

have a right to eat. That is so

because we got used to the idea that charity is all that the poor get and

deserve. Many of us believe that there

is nothing wrong with helping the poor through charity. We should think again.

The confusion between rights and charity harms the poor. By that I do not mean

that it is always bad when an individual acts in a charitable or compassionate

way towards someone in need. My critique is directed to the acceptance of

charity as the institutionalized correct way of dealing with extreme poverty.

To deal with poverty through the help approach is wrong because it treats poor

people as less humans and because it wrongly liberates states from their duties

of justice. Let me tell you a story to illustrate it.

My

mother was born in a poor family in Brazil. In the first seven years of her

life she lived in the country side with her parents and nine other siblings.

During that time life was hard, but they always had food in their plates. When

she was eight years old her family moved to the city, where her and all the

other members of her family got to know a whole other level of poverty. They

did not have food to eat. In order to solve that, my grandma send all her kids

to work for rich ‘good ladies’, which according to my grandma, were very

generous to feed her kids. When I was a young child and I did not want to eat,

my mother would tell me to shut up and eat all that was on my plate. It was

obvious that she could not stand any rests in the plate. It was a few years

after that that I would understand why. The ‘generosity’ of the rich lady that

took her in, under the condition that she would work from morning until night,

was to give her the rests from the plates of her sons. My mother, for almost a

decade of her life, was forced to exist as someone who was only allowed to have

rests. I will not develop it any further, but I can assure you, that such

traumatic experience is still a relevant part of who she is today. It deeply

harmed her identity, what she believes that she deserves from life and the ways

that she is able to interact with others.

Of

course, one could argue that what my mother was exposed to was not charity, but

abuse, and that the consequences of real charity are completely different. But

my mother`s situation was no exception. Many poor kids of her generation were

exposed to the same conditions, and the society accepted such behavior as

charity. Even when we face charity as fully well intended action that does not

include any form of abuse, there is a big asymmetry between the one helping and

the one receiving help. Rights are so fundamentally important because contrarily

to charity rights give people a place in the world. To have a right to eat

means to be in a position where one can demand

food instead of begging for it. Charity, on the other hand, puts the poor

in a situation similar to the one that my mother was in as a child and as a

teenager. And that is the reason why we cannot approach the poverty problem as

a matter of charity. Instead, we need to face this political problem as a

matter of rights.

Charity,

no matter how well intended, always carries the risk of putting the poor in a

place where they are obliged to be grateful for what has been given to them.

Many will say that gratitude is a good thing. That we all should be grateful

for our lives. Even if we accept that this type of claim is true, there is a

big difference in claiming that we all should be grateful in general, and in

claiming that the poor have the obligation to be grateful for our charity.

Gratitude in the first sense can be seen as a kind of psychological tool that

has the potential to help us to enjoy life more fully, whereas the imposition

of gratitude on vulnerable people has the opposite effect. This type of imposed

gratitude also has the effect of marginalizing the vulnerable even further.

That is of course because it interferes in the value that these people give to

themselves. Imagine a poor child who hears over and over again that she should

show her gratitude to that nice lady who gave her bread, to that good man who

gave her soup, or to that blessed child who gave her one of the many Easter

eggs that she received as a gift… Most likely this child will interiorize the

idea that her value as a human being is inferior than that of children who do

not depend on the external help of ‘generous’ people to survive.

To

be honest with you, I do not need to imagine it. I see my mother and all the

scars that she still carries from the time that she did not have the right to

eat. Ten years depending on the charity of nice ladies, who according to my

grandma fed her because they have a good heart and obeyed what God says. For my

mother, those nice ladies, will be forever oppressors. The resentment that that

awful experience left on my mother is so deep that I think she will not ever be

able to see a rich person as an equal. For her, they will be forever those who

walk on earth as they owned it alone. They remain bastards privileged persons

that have no clue about how hard it can be to survive in this world. Thus, to

recognize that the poor have a right to eat can also be a way of start

addressing resentments that the poor feel towards those who wrongly believe to

or are perceived to owe the world. That

is to say, it can be a relevant step in addressing the fact that privileges are

not a synonym of rights.

Comments

Post a Comment